Earth Rights Trek

#1: Route 66 Hostel

#2: Route 66 Hostel Wall Painting

#3: ERT Tents

#4: Clay Ovens

#5: Peabody Operation

#6: Peabody Well for Reservation Residents

#7: Navajo Fast Food

#8: Navajo Fast Food Meal

#9: Solar Stop Sign on Reservation

#10: John, Lorene, Wahela

#11: Lilly's Cob House (1)

#12: Lilly's Cob House (2)

#13: Lilly's Cob House (3)

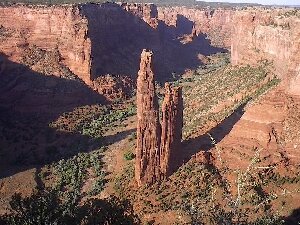

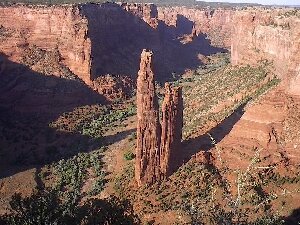

#14: Canyon Spider Rock

|

Earth Rights Trek, Summer 2004 - A journey into native lands of New Mexico and Arizona for dialog and consciousness raising concerning culture, water and land rights and to experience, appreciate and support innovative efforts for sustainable development. This is a day by day description of some of our experiences with some photos following. You can have a cyberspace taste of places visited during our trek by going into the listed websites.

Monday, July 25 - John Fisher, Alanna Hartzok, and Lorene Willis, Director of Jicarilla Apache Nation Cultural Affairs Office drove west out of Albuquerque after lodging at the Route 66 Hostel. (Photos 1 and 2) Our first stop was Acoma Sky City, an ancient pueblo situated on a 367-foot-high sandstone rock. A small bus transported us to the top for a walking tour of this ancient place, which is said to be the oldest inhabited village in the United States. The oral heritage of Acoma tells of the origin and migration of Acoma people in search of HaK'u. Acoma is derived from the Keresan word Hak'u which means to prepare or plan. It was prophesized from the beginning that there existed a place ready for the people to occupy. Recently, archaeologists theorized the occupation of Acoma to AD. 1150. Ceremonial drumming resounded from the center of the village as we walked around hearing about some of the stories and ways of this amazing place. We picked our way down the narrow winding trail and walked back to the car to continue west. Acoma Sky City

We arrived at Zuni Pueblo late afternoon to learn about indigenous land mapping from Jim Enote, who has done conservation work on land, water and cultural issues around the world for many years. Jim is Associate Director, Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative. Here is a good statement from an article on indigenous land mapping:

If map-making by developers and colonial explorers has been a vehicle for the domination of nature and the vanquishing of cultures more sustainable than ours, then perhaps map-making by grassroots groups can help restore the foundations for a sustainable way of life. A starting point is acknowledging history and the central role of culture in influencing how we see the land and those around us. If maps do express our relation to place then community and ecological recovery depends on re-mapping and re-presenting the worlds around us. (Mapping and Eco-Activism - Re-Discovering Our Common Ground)

We put up our tents that night in a light rain (Photo 3) at a campsite near a lovely lake full of wildlife in Zuni.

Tuesday, July 27th - From the Zuni website: Zuni Pueblo is the largest of the nineteen New Mexican Pueblos, with more than 700 square miles and a population of over 10,000. We are considered the most traditional of all the New Mexico Pueblos, with a unique language, culture, and history that resulted in part from our geographic isolation. With perhaps 80% of our families involved in making arts, we are indeed an "artist colony".

We learned a lot at the excellent and very interesting Zuni Ashiwi Awan Museum and Heritage Center. I purchased a lovely female healing kachina sandpainting and Lorene bought turquoise earrings at one of the many wonderful shops along Zuni main street. Photo 4 shows traditional bread ovens seen near homes throughout the region. Then we headed for Gallop to load up on fresh fruit and vegetables for our Hopi and Navajo friends at Second Mesa, where we arrived that evening and had dinner with Wahleah, one of the Navajo leaders of the Black Mesa Water Coalition.

Happy for the lovely rain falling in this dry region, we spent the night at the Hopi Hotel on Second Mesa.

Wednesday, July 28 - The Hopi Reservation, in Northeastern Arizona, encompasses approximately 1,542,306 acres of which 911,000 acres is identified as the Hopi Partitioned Lands. The Hopi people have lived in this area for over a thousand years. The Hopi Reservation is surrounded on all sides by the Navajo Reservation which encompasses about 25,000 square miles, about the size of West Virginia, and is the largest rez in the US. Located primarily in Arizona, the reservation also extends into Utah and New Mexico. There are approximately 200,000 Navajo people, who call themselves "Dine".

Early morning we met Wahleah for breakfast, along with Lilly, a Hopi founder of Black Mesa Water Coalition and others. John, Lorene and I then climbed aboard Wahleah's four wheel drive truck for our tour of the Peabody Coal mining region of the reservation. Seeing for ourselves this water conflict situation was one of the main purposes of our trip. Here is what the Navajo and Hopi young people of the Black Mesa Water Coalition are concerned about:

From Black Mesa Water Coalition:

Each year Peabody Coal Company pumps more than 4,500 acre-feet of pristine Navajo and Hopi drinking water from the "N-Aquifer". Peabody uses this pristine water supply simply to mix with crushed coal-called "slurry". This "slurry" is then pumped through a pipeline over 275 miles to the Mohave Generating Station in Nevada. Diné & Hopi WATER and COAL supply electricity to cities of the Southwest‹Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Las Vegas. This is a sole source of drinking water for the Navajo and Hopi people who live on and around Black Mesa.

Black Mesa Water Coalition (BMWC) has been working to end Peabody Coal Company's wasteful use of scarce & sacred ground-water. BMWC is calling for a transition to renewable energy practices and sources. BMWC is calling for a transition to more sustainable employment and economic sources."

As Wahleah explained to us, the acquifer level is dropping steadily each year. In this semi-desert area, continuing loss of these huge quantities of water threatens the ability of the people to continue to inhabit their lands. Currently people must travel long distances to the one well that Peabody has erected for the people to draw water from. They truck water for their livestock and personal survival needs sometimes on a daily basis. Photo 5 shows the Peabody Corporation main operations center where the coal is mixed with the water and begins its 275 mile trip through the pipeline. Photo 6 is the water pumping place for the Hopi and Navajo people.

Photos 7 & 8 show fast food Navajo style where we stopped for a meal of mutton corn soup and blue corn mush. Photo 9 is a solar powered stop sign, a hopeful hint for a possible future in this land of much sun and little water. Photo 10 shows Wahleah, Lorene and John at a scenic lookout.

Wahleah then drove us to her family ancestral lands where we visited with her grandmother in her newly built hogan, a traditional dwelling usually six-sided. Wahleah explained how it is that her grandmother speaks Navajo language and no English. When the colonizers came to the area to take the children to boarding schools, her grandmother's parents instructed her to run away and hide in a remote area and thus avoided capture.

After seeing her grandmother we spent some time by a spring near where Wahleah and her father and others intend to build a new settlement.

We drove through more breathtaking scenery, including small herds of sheep, cattle and horses moving freely along and across roads. Next stop was the substantial new high school with a well-stocked computer lab where Wahleah's mother is principal. With sadness in her voice Wahleah told us about the relatively high suicide rate among the youth of the suburban-like village of Pinion where the school is located. Black Mesa Water Coalition is also working to introduce Navajo cultural and healing ways to the youth of Pinion.

Returning from the Navajo lands we went back up to Second Mesa in Hopi territory to Lilly's parents' house beside which Lilly is building her own house. Lilly had taken a nine week course in cob building in Oregon and had returned home to make good use of her new skills. See Photos 11,12, 13 of Lilly's Cob House, which will soon be completed.

While we had been investigating the Peabody operation, Lilly had been cooking all day to provide an evening meal for the Peace and Dignity Runners, a group of about thirty native people from several tribes who had begun their journey months ago in Alaska. They would be arriving in Panama in early autumn to meet with a South American group running north.

From History of Peace & Dignity Run:

There was a prophecy that the Eagle and the Condor time was nearing. This time was marked and recorded on the Sacred Stone Calender of the Mexica People. The Calender has time spans of 52 year cycles. The last cycle was nearing his end on October 12, 1992. The new cycle began October 13, 1992. Within this new cycle would be a time of rebirth of conciousness amongst the two-legged and the Eagle and Condor Prophecys would be manifested in this time. A spiritual run every four years (first one was in 1992) was envisioned as a prayer for healing and the a way to fulfil the Prophecy of the uniting of the people of North and South of this hemisphere. "No one after 500 years of misery is all holy or all healed.... Remember we are in a healing process of decolonization and are not looking for some great leader to come out of the sky and tell us what to do."

We put up our tents in a camping area right beside the Hopi Hotel. It was our great blessing that the Peace & Dignity Runners camped there that night, too. We had meaningful conversations with several of them near the fire under a bright moon.

Thursday, July 29 - Our destination today: Canyon de Chelly. Continually awed by the scenery as we journeyed from Second to Third Mesa, we stopped in Old Oraibi and purchased kachinas, craft items and beaded bracelets before continuing on miles of earthen roads down into and through the Navajo Reservation. Driving along I reflected on what I had been learning about native land tenure on these reservations. I am just learning about the details, so please don't quote me on the information in this next paragraph.

Reservation land is held as trust territory for native people by the US government. Individual Navajos do not own the land upon which they live as families hold traditional use rights under tribal customary law. Nearly all land on the reservation is part of someone's traditional use area. Traditional inheritance rights are to the youngest daughter. (Interesting how this is the exact opposite of patriarchal inheritance to the eldest son.) The women allocate the land use areas for homesites. For instance, if someone wants to build a house, the female would give the permission for a particular location. Reservation land is certainly not bought and sold, nor does it seem to be leased among natives. When we met with Jim Enote in Zuni village, the land he was building his new house on was simply allocated, not purchased. Lilly was building her cob house right beside her parent's house. So there is no need for mortgage and interest payments for land access. There seemed to be no zoning codes or required building permits either, at least that was my impression, but again, please don't quote me on this.

Wahleah had mentioned something about "a sleeping giant" referring to the Navajo people and lands. With the vision of sustainable development using local materials, solar energy, and food self-sufficiency that she and other native young people we met were beginning to actualize, it seems there could be a healing and rebirth of the spirit and people of these lands. I had first met Wahleah in April at the United Nations where she was participating with other Native Americans in the World Commission on Sustainable Development. I had caught sight of her in a UN hallway around the time I had been intending to make contact with someone from Black Mesa. Perfect! But there at Black Mesa Wahleah told us that there could be trouble ahead. There is some concern that the US government might try to withdraw reservation treaties in the next few years. We all have to be alert to this and ready to defend those treaties!

A relevant quote from Lilla Watson, Aboriginal Australian Wisdomkeeper:

"If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together."

And that is also my knowing and perception about our experiences and new friendships on Black Mesa.

Arriving mid-afternoon in the town of Chinle, we pitched our tents at Cottonwood Campground and left for an auto tour along the South Rim of Canyon de Chelly, pronounced "da shay."

Canyon de Chelly is awesomely beautiful, with sandstone cliffs embracing more than 200 million years of geological history and nearly 4,000 years of human history. It took us a few hours to view the seven overlooks along this 16 mile drive, from which we could see ancient dwellings built between 350 and 1300 AD at the base of sheer red cliffs and high up in canyon wall caves. The most sacred is the White House which figures prominently in several origin stories and ceremonies of the Navajo. We met some of the people who live and farm on the canyon floor who were vending beautiful art, craft and jewelry at several lookout points. At the end of the South Rim road we spotted a sign for horse rentals and drove into Totsonii Ranch. Lorene and I started to think about a morning ride into the canyon. It was getting late and we were hungry, so we shopped in Chinle for cook-out supplies and feasted that night on roasted mutton ribs, corn on the cob, and green chilis.

Friday, July 30 - Bright and early (well, around 10:00 am) Lorene and I were riding mustangs with a Navajo guide down a narrow, winding, rocky trail from the rim of Canyon de Chelly into the valley below. We let the horses rest near the base of 800 foot Spider Rock (Photo 14), a sacred site, while we looked at petroglyphs on the canyon walls. Saddling back up, we rode the horses to a small stream where they watered, then trotted on the trail through the sagebrush, juniper and moonflowers in that part of the canyon, making our ascent back to the rim around 2:00 pm. It was the ride of our lives! View where we rode here: Totsonii Ranch

After a late lunch at Thunderbird Lodge we toured the North Rim of Canyon de Chelly, then headed east to Albuquerque, looking back occasionally to view the show of a southwest sunset. Lorene said she was inspired with ideas for her work as Director of the Jicarilla Apache Nation Cultural Affairs Office. She had thoroughly enjoyed the trip, as had John and I, and we had thoroughly enjoyed her companionship! We talked about maybe visiting with her on the Jicarilla Apache reservation sometime. Saying our farewells at her truck, Lorene gave us a bag full of savory buffalo jerky from the animals on the Jicarilla reservation.

Route 66 Hostel was Friday evening accomodations for John and I. We shared a few thoughts for a possible Earth Rights Trek #2 before he left on the bus for British Columbia Saturday morning.

I visited the Albuquerque Museum and the National Atomic Museum on Saturday, drove to Taos and toured El Monte Sagrado (because of special interest in seeing their "biolarium") on Sunday, thoroughly enjoyed old town Santa Fe Monday morning, and arrived at the Albuquerque Sunport in time for my Southwest flight back to Baltimore-Washington Airport Monday afternoon.

All in all, I fell in love with the Southwest and am already looking forward to being there again. If you might like to join us for Earth Rights Trek #2, call me at 717-264-0957 or email to: .

In earth's embrace,

Alanna Hartzok, Co-Director

Earth Rights Institute

alanna@earthrights.net

Earth Rights Trek to Acoma, Zuni, Hopi Pueblos and the Navajo Nation in New Mexico and Arizona

August 26 to 30, 2004

Report by John Fisher fisherjmca@yahoo.ca

From July 21 to 25 about 100 North American Georgists (1) gathered in Albuquerque,N.M. to hear speakers and take part in panels and discussions related to the Conference theme, Health, Wealth and Land: Reclaiming Our Common Heritage.

The Conference addressed social issues like urban sprawl,housing and the military presence in New Mexico. The focus on the misappropriation of natural resource rents into private hands instead of the public domain (see Georgist footnote) set the tone for the post conference Earth Rights Trek.

The Trek was billed as a "journey into native lands of New Mexico and Arizona for dialog and consciousness raising concerning culture, water and land conflicts and to experience, appreciate and support innovative efforts for sustainable development."

As one of three participants the Trek achieved its objectives and more! Trekkers included Alanna Hartzok,Co-Director of Earth Rights Institute (2),V.P. of the Council of Georgist Organizations (Conference sponsor) and U.N. NGO Representative for the International Union for Land Value Taxation; Lorene Willis, Director Jicarilla Apache Nation Cultural Affairs Office(3); John Fisher, President of the Henry George Foundation of Canada (4) and contact for the Wet'suwet'en First Nation in British Columbia (5).

In a rented car the trio visited the Pueblos of Acoma, Zuni, Hopi, the Navajo Nation and the National Park, Canyon de Chelly (d'shay) where so much Southwest native history began.

The Anasazi (the ancient ones) mysteriously abandoned their occupation of the Canyon de Chelly after six hundred years of building cliff dwellings and developing their culture. Around A.D. 1200 these farming people migrated to become AcomaZuni and Hopi ancestors. The Acoma Pueblo (Sky City) and Hopi Pueblo (Old Oraibi) both claim to be the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America.

The Navajo (Dineh) and Apache Nations are both related culturally and linguistically to the Athapascan of northern Canada. The Navajo wanderings and culture were constantly being influenced by other groups of Indians with the same language and by refugees from peaceful farming Pueblos.

The cultural and economic history of the Pueblos and Nations have been directly linked to their access to the natural environment (i.e. villages on mesas, agriculture on canyon floors). When the natural resource base,which supports people everywhere,is disrupted by natural disaster or conquest local people suffer. Today mankind has reached a scale of development that threatens the whole globe (nuclear war, climate change, environmental destruction).

In the past it was the Spanish that conquered the various Pueblos (6) while it was a young U.S. government that finally squeezed the Navajo into Canyon de Chelly and exiled them to Fort Sumner (7).

Today the Navajo,the Pueblos and other native groups are slowly reversing the social and economic injustices imposed upon them over the last few hundred years. They are returning to their roots which include their oneness with Mother Earth. It is both a spiritual and an economic renewal.

In north central B.C. the Wet'suwet'en First Nation are developing a sophisticated and comprehensive Territorial Stewardship Plan. Ever more frequently the non-native community wants to consult with the Wet'suwet'en about forestry and other development matters.

The Plan is not without its critics even within the native community but by using GIS technology to identify and plot detailed cultural and resource data it is hard to ignore the Plan when even the provincial government often does not have this depth of information.

While camping at Second Mesa near the Hopi Cultural Centre Trekkers met indigenous runners who had passed through Smithers, B.C., on their way from Alaska to Panama. The Peace and Dignity Run,according to organizer Jose Malvido is a spiritual journey. One runner said, "I sing and pray to the mountains and they sing back."(8)

By raising the awareness of indigenous rights with events such as the Run it also helps to focus attention on 'Earth Rights'.

The Hopi and Navajo are locked into a dispute with Peabody Coal Company about water. Peabody mines coal near Black Mesa, Arizona,reduces it to a powder and mixes it with water taken from the Navajo Aquifer which is under the Hopi and Navajo reserves. This slurry is then transported in an eight inch pipe westward 300 miles to the Mohave Power Station in Nevada.

Wahleah Johns (Navajo) took the time to drive the three of us to the mines and explained some of the impacts this whole operation is having on the local people. Problems include secrecy and double dealing lawyers, cultural differences as to how resource values are measured (lease values are too low), effect of blasting on livestock, burial and sacred sites disruptions, air pollution (coal) and subterranean collapses which result in salt contamination of aquifer water.

The Black Mesa Water Coalition (9) and other concerned groups are now fighting 21st century injustices and are preparing for the water lease renewal discussions in 2005. As in the 1500's the central issue is still about the natural resource base--the land. What is its worth to society and how should that value be collected and distributed among the stakeholders?

To overcome language differences and the information gap the Navajo are bringing these issues to the Clan Chapter Houses. These Houses are scattered around the reservation(s) and it is here discussion takes place and advice is forwarded to tribal elders.

At the Zuni Pueblo we met with Jim Enote(10). He stressed the importance of community based economics and decision making. He also cautioned that in many native communities knowledge is limited to clan religious leaders (gatekeepers). This sometimes works against progress but also the Zuni have survived for thousands of years by embracing conformity and uniformity (tradition).

Many natives and non-natives recognize that knowledge is power and one example of this has been the use of maps. As Jim says,"more indigenous land has been lost with maps than in battles."

Quality of life is linked directly with Mother Earth. How we use our common heritage and how we distribute the social rent (11) created from it is best left to the community that identifies most with the local resource base.

In most indigenous communities,traditional use patterns have served the clan or tribe well. However First Nations need a resource inventory (including accurate mapping) so they are able to deal with outside influences of developers and corporations. Non-native communities need similar resource information data.

Since the concept of a monetary value for resources has never been an indigenous tradition, values should be based not only on supply and demand but on cultural and other social values. For example what value does a burial ground have? What is the value of a wetland or a wood lot? The Wet'suwet'en are currently developing such measurement techniques.

The questions above need to be answered by all communities so elders and/or governments can make wise decisions for their people.

Footnotes

(1) The term Georgist refers to someone who identifies with the economic analysis and social philosophy advanced by the North American economist Henry George. The Georgist philosophy advocates equal rights for all and special privileges for none. It affirms a universal right for all to share in the gifts and opportunities provided by nature.

Central to this philosophy is the conviction that social problems must be traced to their root causes and remedied at that level,rather than dealing with mere symptoms. The science of political economy,whose task is to explore such root causes,must be understood not just by experts but by everyday people so that injustice and corruption cannot be foisted on an unwitting public. Economic analysis shows that natural resource values of land,air,water,etc. are due to natural and social processes, should be the source of public revenue and that taxes on labour, thrift and industry should be eliminated. Properly understood,economics should be a guide for achieving justice and sustainable prosperity.

Council of Georgist Organizations

P.O. Box 57,Evanston, Illinois, 60204

Phone: (847)475-0391 Email: swalton@surfbest.net

(2) The biggest challenge for social democracy today is to articulate coherent policies based on a unifying vision for society. Major problems include 1)the enormous worldwide wealth gap and the underlying concentration of land and natural resource ownership and control and 2)building global governance institutions and financing governance and development which strengthens social structures and environmental restoration.

A basic clarification of First Principles should start with the principle that land and natural resources of the planet are a common heritage and are a birthright to everyone.

Products and services created by individuals are properly viewed as private property. Natural resource values as created by the presence and activity of the community should be collected as a 'Social Rent' to support required government.

Earth Rights Institute

Box 328, Scotland, PA, 17254, U.S.A.

Phone: (717)2640957 Email: alanna@earthrights.net Website: www.earthrights.net

(3) Jicarilla Apache Nation Cultural Affairs Office

P.O. Box 507, Dulce, New Mexico 87528

Phone: (505)759-1343 Email: lorenew@jicarilla.net

Website: www.jicarilla.net

(4) Henry George Foundation of Canada

P.O.Box 122,

Rodney, Ontario, N0L2C0, Canada

Phone: (519)785 0203

Email: jmfisher@execulink.com or fisherjmca@yahoo.ca

(5) Office of the Wet'suwet'en, Lands and Resources Department

Andy George, Jr., Manager

25 Beaver Road, Smithers, B.C. V0J2N0, Canada;

Phone:(250)847-3630 Email: ageorgejr@wetsuweten.com

(6) In 1680 the Pueblos finally revolted against their Spanish conquerors. When the revolt was put down 12 years later many Pueblo moved in with their neighbours and traditional enemies the Navajo bringing with them their sheep and expert knowledge of weaving. Some of Navajo culture may have originated with this contact.

(7) By mid 1700's pressure from warring northern tribes and population increases forced the Navajo westward and the occupation of northeast Arizona, including Canyon de Chelly began. In 1864 the U.S. Army was called upon to "subdue the Navajo." The Navajo were marched nearly 400 miles to Ft. Sumner where they suffered imprisonment for four years. In 1868 a treaty was signed which allowed the Navajo to return to the defined reservation.

(8) Smithers Interior News article, June 2, 2004 Box 2560, Smithers, B.C.,V0J2N0 Phone: (250)847 3266

(9) The Black Mesa Water Coalition has been working to end Peabody Coal Company's wasteful use of scarce and sacred groundwater. The Coalition is calling for a transition to renewable energy practices and sources. It is calling for a transition to more sustainable employment and economic sources.

P.O.Box 895, Kykotsmovi, Arizona, 86039

Phone: (928)226 0310 Email: blackmesawatercoalition@yahoo.com

(10) Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative

Jim Enote, Associate Director

P.O. Box 1068, Zuni, N.M. 87327

Phone: (505)782-5675 Mobile: (505)980-2553 Email: enote@igc.org

(11) For definition of Social Rent see Georgist and Earth Rights Institute footnotes.

Return to Earth Rights Homepage

Last modified: 4 September 2004

http://www.earthrights.net/trek.html